Bill Freehan: The Tiger Who Was a Horse

11/29/2017 1:57:00 PM | Baseball, Features

By Steve Kornacki

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- Bill Freehan was considered the premier catcher in baseball until Johnny Bench came along and claimed that title.

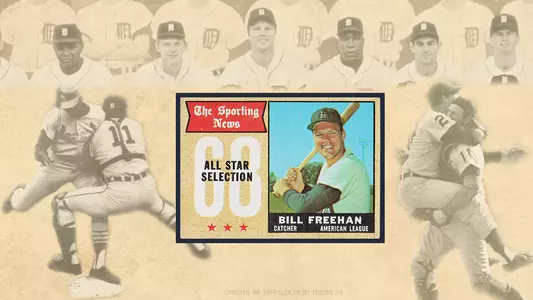

He began a run of 10 consecutive All-Star Game selections in 1964 -- just three years removed from his time as a University of Michigan two-sport standout -- and finished third in American League MVP voting in 1967 and second in 1968, when his Detroit Tigers won the World Series.

Freehan would've been a back-to-back MVP selection in many seasons. However, Boston's Carl Yastrzemski won the Triple Crown in 1967, and Tigers teammate Denny McLain won 31 games the next year to claim those awards.

Still, Tigers Hall of Fame right fielder Al Kaline paid Freehan a compliment that very well could top any award.

"Over a long period of time," Kaline said in a recent phone interview, "Bill was the best player I ever played with on our team. He was such a great leader of our team. He wasn't (officially) the captain, but he was the captain of our ball club.

"He was truly a great Tiger, and he should have something where people will always remember Bill Freehan as a great Detroit Tiger."

Freehan was front and center in both of the most iconic photos from the '68 World Series, and wouldn't it be fitting if one of them was commemorated at Comerica Park in Detroit with a statue?

Freehan blocked home plate, standing "like the towering Washington Monument," wrote United Press International columnist Milt Richman, before tagging out St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Famer Lou Brock at home plate in the pivotal play in Detroit's Game 5 comeback victory.

"Willie Horton did a great job of charging the ball (in left field) and making a very accurate, one-hop throw to Bill," said Kaline. "He blocked the plate, and many people felt that if Brock had slid, he might have been safe. It was a very controversial play, and Brock still says, when I see him up at Cooperstown, that he touched the plate. But with Bill having his foot planted there, it looked like he spun Brock around off the plate."

Brock, one of the game's premier base-stealers, elected to come in standing up, and Freehan didn't budge. Home plate umpire Doug Harvey called Brock out. My father took me to the Detroit Auto Show that winter, and I had Freehan and Brock both autograph a color photo of the play that ran in the Detroit News. Brock signed his name on home plate and smiled after making his point.

"I was surprised he didn't slide," Freehan was quoted as saying after the game. "There I was, set. With my left foot planted where it was, he'd have had to slide through it or touch the plate with his hand, simply because I was between him and the plate. When he hit me on the left side, he just spun away from the plate. The reason I tagged him a second time was I saw him coming back -- like a reflex, you know?"

Detroit trailed, 3-2, in the top of the fifth inning at that point. It scored three runs in the seventh inning for the win, outscored St. Louis, 20-2, from that point forward, and became world champions with three consecutive victories.

Freehan caught the final out of the 4-1 triumph in Game 7 by tossing his mask aside and running to his right to nestle under a foul popup by Tim McCarver. Immediately after grabbing the ball, Freehan wheeled around and took a step near the foul line before World Series MVP pitcher Mickey Lolich joyfully jumped into his arms.

"You catch it," Freehan said afterward, "and the world jumps on top of me, and obviously that's the highlight of your career. When Lolich jumps on you, he's not a small man! But it was a great feeling! It was a big thrill."

Freehan carried the hefty Lolich, whose arms and legs were wrapped around him, about 20 feet into the victory celebration that soon engulfed them and included Kaline and backup catcher Jim Price.

"It's what everybody wants to be: a world champion," said Kaline. "With Bill under it, we knew he was going to catch it. And Mickey Lolich was just unbelievable in the Series. He started, finished and won all three games. It was just that feeling that I'd finally done it, became a world champion, and I was just elated and couldn't get to the clubhouse fast enough with those guys to celebrate."

Price, the long-time Tigers radio analyst, said, "We were all young, and to come back against a very special St. Louis team (the World Series winner in 1967), that was a special group. Our 50th anniversary is coming up next year, and Bill was our leader. When Lolich jumped into Bill's arms, we weren't far behind. That was a very special moment."

That was a half-century ago, and now, two generations later, Tigers fans might get to see the spitting image of Freehan, who turned 76 today (Wednesday, Nov. 29), in the years ahead.

His grandson, Blaise Salter, is a rising star first baseman in the Detroit farm system. He was a Midwest League All-Star in 2017 for West Michigan, batting .330 with six homers and 53 runs batted in before getting moved up to high Class A Lakeland.

Blaise, who was mostly a designated hitter at Michigan State but also caught and played first, was wearing the crucifix on a chain that his grandfather wore during his career when the Tigers made him a 31st-round draft pick in 2015. It was a gift from his grandmother that has since been returned for fear of losing the treasured cross.

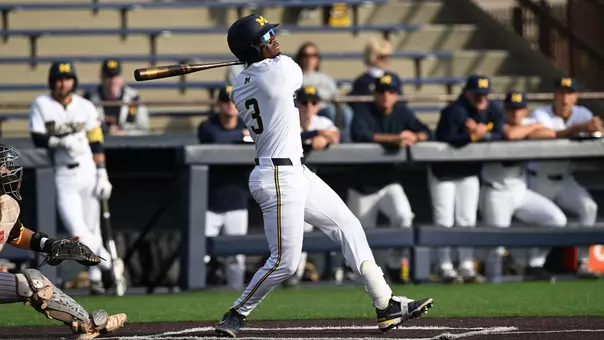

He has a similar hefty build to his grandfather, who was 6-foot-3 and 203 pounds, and it's uncanny how alike their swings look.

"Yes, in his hitting and his swing and in his stance at the plate," said Pat Freehan, Bill's wife of 54 years. "I saw a photo of Blaise following through on a swing and said, 'Oooh, Honey, you look just like Papa there with the square jaw, too.' It just warms my heart to see that, and it brings back wonderful memories."

Blaise's youngest brother, Harrison Salter, redshirted last year as a freshman at Michigan and is a catcher just like his "Papa," as their grandchildren call him. Middle brother Will Salter is a catcher at MSU entering his senior season.

"When I was growing up," said Harrison, "Papa would come to my games. But he would never get in my face after games. He'd wait about one hour and give me three or four things I could improve upon. They were always concrete things I could work on. I just want to work so hard and give my best so that maybe someday I can be in some way like him in baseball aspects."

Freehan with wife Pat and grandson Blaise Salter

William Ashley Freehan played only for the Tigers in 15 seasons, and he was an 11-time All-Star who won five Gold Gloves. He batted .262 with 200 homers and 758 RBI for his career, and he hit .300 in 1964. Freehan's most productive season was 1968, when he had 25 homers and 84 RBI and led the American League in hit-by-pitches with 24.

"He stood close to the plate and did not have fear in the box," said Kaline. "That's why he got hit a lot. He was a tough competitor who always drove in the big runs. He never led the league in RBIs but was close to having the most on our club."

Freehan also was one of the game's premier defenders.

"There were his leadership qualities and the way he called the game," said Kaline. "Defensively, he blocked the ball well, and he had a quick, accurate arm."

Price added: "He had a great glove hand, and he used the old 'pancake' glove that didn't have any flex in it and very little webbing. That shows you how great his hands were. He'd catch everything right in the pocket. He amazed me with having such great hands and the way he handled pitchers with that type of glove. It was phenomenal, it really was."

He also worked with two of the best strikeout pitchers in baseball: Lolich and McLain, the only hurler to reach the 30-win plateau in the last 83 years.

Freehan retired after the 1976 season, having played together for over one decade with a talented group: Kaline, Horton, Lolich, Dick McAuliffe, Mickey Stanley, Norm Cash, Jim Northrup, John Hiller and Gates Brown.

"They were just such special times," said Pat. "Bill always said that growing up in Detroit and playing for Detroit was a dream. He used to hitchhike from 12 Mile Road and Woodward to watch the Tigers."

They all became close friends for life.

"There were a lot of loving things that Bill did," said Kaline. "The way he carried himself was special. First of all, he was very smart. He was such a great guy to be around.

"Bill and I used to ride into the ballpark together all the time, and just to hear him talk about all the hitters and his knowledge, I always thought Bill would've been a great (major league) manager someday if he wanted to. But he was just a great friend and a great family man.

"He was a team guy, and he was a horse. He played almost every day and got hit by pitches a lot, but he always wanted to be in the lineup, and you knew that when he was in the lineup he was giving everything he had."

That word, "horse," came up quickly when Price described him, too.

"He was such a horse," Price said. "It seemed like he never got tired, and I used to kid with him: 'I'm going to push you down the steps so I can get into a game.' And he would laugh. He commanded a lot of respect -- a lot of respect."

Freehan played in 155 games both in 1967 and 1968 and missed just seven games each season, roughly one per month.

"So," said Price, "guys would kid me and say I hadn't played in a while. I'd say, 'Yeah, but I'm backing up the best catcher in baseball, so I must be pretty good.'"

Price laughed.

"I just had so much respect for him," he said. "I always will."

Price, his teammate for five seasons beginning in 1967 after a trade with the Pittsburgh Pirates, said, "When I came to the Tigers, I didn't know much about Detroit, but I knew about Bill and what a great catcher he was. I thought about all I could learn from him, and the first thing that struck me when we met was what a nice guy he was.

"Then, through the years, having a great relationship, I remember the good times. He was always smiling and loved to play."

Freehan was "a horse" and their leader, somebody to be counted upon for his play and his actions.

He would help groom Detroit's next great catcher, Lance Parrish, at the request of Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson. So, his impact on the Tigers continued with their next World Series championship in 1984. Now, with his grandson, the franchise might well keep reaping the rewards of having Freehan bloom in their organization.

His is a story that keeps coming back full circle.

• Bill Freehan: A Legend and His Legacy -- Read about Bill Freehan's University of Michigan years, family life, and the love of his wife, Pat, as they battle the rigors of Alzheimer's disease.