67 Years Later: Lt. Hal Downes, MIA in Korea, Gains Spot in Hall of Honor

11/14/2019 1:13:00 PM | Ice Hockey, Features

A 1951 NCAA champion and All-America goalie whose name has been attached to the Michigan ice hockey Most Valuable Player trophy for more than 60 years, Hal Downes will be inducted into the Michigan Athletics Hall of Honor during a Friday (Nov. 15) ceremony along with Erick Anderson (football), John Fisher (wrestling), Lara Hooiveld (women's swimming & diving), Ron Simpkins (football), Stacey Thomas (women's basketball) and Nick Willis (men's track & field, cross country).

By Steve Kornacki

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- The University of Michigan ice hockey Most Valuable Player has been accepting the Hal Downes Trophy for more than 60 years. Legendary players such as Red Berenson and Marty Turco have won it, and so have Hobey Baker Award winners Brendan Morrison and Kevin Porter.

It was named for Downes -- an All-America goalie who helped lead the Wolverines to their 1951 national championship while also garnering all-tournament honors -- in 1956, when his coach, Vic Heyliger, was winding down his career as Michigan's first Hall of Fame coach in the sport.

However, Downes, who will be inducted into Michigan's Hall of Honor on Friday (Nov. 15), never got to hand out the award bearing his name.

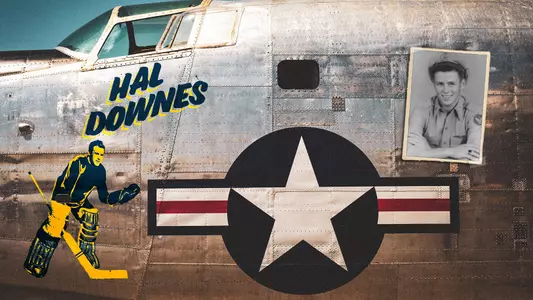

Less than 10 months after Downes turned away 19 shots by Brown in a 7-1 championship game victory at the Broadmoor Ice Palace in Colorado Springs, Colorado, U.S. Air Force Lt. Downes went down with three others in a B-26 Marauder over North Korea. He has been listed as missing in action (MIA) since Jan. 13, 1952.

"I admired him even though I wasn't around him that much," said his son, Rick Downes, 71, president of the Coalition of Families of Korean & Cold War POW/MIAs. "There was a mystique to someone you grow up missing like that."

Hal's daughter, Donna Knox, helped found that organization in 1998 and remains involved. Along with her brother, she has helped countless families that share "a wound that never heals." Some 45 years ago, she amazingly received her dad's '51 NCAA championship ring that was once locked away accidentally with another airman's personal belongings, but her father's exact fate remains unknown 67 years later.

"Our mom did a beautiful job of keeping our dad alive for us," said Knox. "Because he was MIA and not KIA (killed in action), we kept waiting for him to come back. She did us that favor and probably made our loss more severe. But I have my dad in that fashion, and for that I am forever grateful. It's a bond Rick and I share.

"My dad was, by all accounts, a good guy. He was a devoted husband and father and a real sports enthusiast (he also loved golf), a hard worker. In our lives, he is like a god. He was handsome, and he's on a pedestal that no one will ever take him down from. I never met him, but like everything about him and know him in my heart."

They plan to attend the Hall of Honor ceremonies for the father they cherish mostly through the stories of their mother, Elinor.

Elinor met Hal when they were teenagers at a church youth group gathering in Stoneham, Massachusetts, and married him before life brought them to an apartment on Hill Street in Ann Arbor shortly after Rick was born.

Downes in goal for the Wolverines in the 1951 NCAA championship game against Brown.

There was some serendipity connected to the family learning of Hal's Hall of Honor selection.

"We had just pulled out his national tournament championship award for the team winning," said Downes, an elementary school teacher who also did some acting and writing. "It says, 'National Collegiate Ice Hockey Championship, 4th Annual Tournament, '51.' It's on a plaque and it's very cool.

"I was just blowing the dust off it and putting it up right next to my computer monitor -- and it's a big, heavy piece of wood -- and the call came telling us Dad was in the Hall of Honor. So, it was very emotional and exciting. The event itself is going to be exciting."

Knox said, "It's hard to put what I feel into words. It's where he belongs. I imagine it's a combination of his play and what he did for the hockey team and what became of him afterwards. But I think that the two go together. It shines on the University that one of their own -- especially a star athlete of their own -- went on to make the ultimate sacrifice for his country.

"I'm just so proud and really grateful that the University he loved so much is bestowing such a special honor on him. It's fitting and makes me smile on the inside. My dad loved the University of Michigan through and through and was very proud of the team."

Downes' 1951 NCAA championship plaque

Elinor died last year at the age of 92, but she did return in 1998 along with Knox to present that year's Hal Downes Trophy to Turco, the All-America goalie who had just led the Wolverines to a second NCAA championship in three years before going on to star in the NHL for the Dallas Stars.

"That was a real honor and pretty surreal," said Knox, "and it was also heartbreaking."

Knowing her father wasn't there with them, too, tugged at her.

"Is the wound ever going to heal?" she asked. "And it just doesn't go away. We don't, in our hearts, have much hope anymore that our dad is alive. But we still want to know what happened to him. It's incumbent on our government to find him."

Their life in Ann Arbor was like something out of "The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet," a popular TV show that ran from 1952-66 about an All-American family and its growth through the years.

Downes said, "It was very special. Our first three years together -- between my mom, dad and myself -- were in Ann Arbor. We stayed there until he was recalled (for the Korean War), and my sister, Donna, wasn't born until three months after he was missing. She had never been to Ann Arbor before that award presentation.

"We have pictures of Hill Street and all the different things that went on in our lives there. So, it was very special for her to go back with Mom then. I went back once, and the building on Hill Street is still there. We are very proud that the MVP award is named for Dad."

There's a special photo of little Rick, bundled up for winter and standing in front of his father wearing full hockey uniform and equipment. Dad is leaning in over him, goalie stick in his right hand.

"My dad had all kinds of jobs on campus," said Downes. "He worked in a book store and turned the lights out in the arena (The Coliseum used by the hockey team until 1973 and still in use at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Hill) every night.

"He also sold programs at the football games, and my mother said he would be so excited he would actually be shaking. He would come and sit in the stands with her after selling them and just be so excited. He loved the football games."

Rick Downes with his father (top) in Ann Arbor and with his sister, Donna, next to a photo of Hal.

Heyliger, who won the first six of Michigan's NCAA-record nine national titles, was from Concord, Massachusetts, and had strong ties to his home state, helping lead him to Downes, who played at Stoneham High, just north of Boston.

"He went to what was called a junior college back then for his first two years," said his son. "When he got back (from serving during World War II), my mom and dad got married and went to an auxiliary of the University of Massachusetts for a two-year program. When he got out of that, he received two-year scholarship offers and accepted one to the University of Michigan. He was a business administration major.

"Mom had me, her baby boy, to take care of. But she definitely went to some games, and then he went off to Colorado Springs for the championships."

The Wolverines beat Boston University, 8-2, in the semifinals before winning the title in another six-goal blowout of Brown. Senior Neil Celley and sophomore John McKennell both scored twice in the championship game. Celley led the NCAA and set a Michigan record with 79 points while scoring 40 goals in 27 games. McKennell had 35 goals and senior captain Gil Burford had 37 on a powerful offense.

It was a team that had it all, and Jim Barker of the Michigan Daily credited defensemen Bob Heathcott, Alex MacLellan and Graham Cragg for their efforts. Brown did not get a shot on goal until 15 minutes into the game. Downes, who wore No. 1 between the pipes, then stopped just about everything that came his way to complete a true team effort.

His son has the heavy wooden plaque presented to his father and other members of the '51 national champions.

His daughter has the '51 NCAA championship ring, thanks to Ken Enoch, a Texan who was the navigator on her father's ill-fated bomber.

"When the plane was lost," said Knox, "they packed up all their stuff, and the ring got locked up with Ken Enoch's stuff and accidentally sent to his house. He was released after the war, went through his stuff, and he found that ring. He didn't know what it was or whose it was and just put it up in his attic."

Downes' 1951 NCAA championship ring, mistakenly given to the navigator on his ill-fated bomber, "was the one part of him that came home."

And that's where the mystery ring stayed from the end of the Korean War to the end of the Vietnam War. That's when Knox called Enoch to get in touch, and he mentioned a ring that he wondered about. He thought they were crossed golf clubs on the side, but Knox said they were more than likely hockey sticks. Enoch told her he would look for the ring and get back.

"Then the package with the ring in it arrived at the house," said Knox. "My father's initials (HWD for Harold Webb Downes) were right inside it.

"It's the one part of him that came home."

Knox also has Dad's No. 1 Michigan jersey, skates, Michigan cap and goalie glove. The ring became a constant reminder of her father, and she wore it daily on her right hand until alternating it with the jade and silver ring her late husband, Cecil, always wore.

"Every year on the day and time my dad's plane went down," she said, "I go off by myself and commune with him somewhere in nature. It could be woods or cliffs by the ocean. Sometimes just a quiet lagoon. I always bring his picture and his hockey mitt. As I sit there, I slip my hand into the glove, knowing his hand was in it so many times, which makes me feel close to him."

They've carried Dad's memory all these years, too, holding on to a man so worthy of admiration who was gone long before any of them were ready to let go.

"He has been missing all of our lives," said Downes. "So, it's not like he was dead. Missing is almost worst because you're still in the minds of your loved ones when you're gone. As a youngster, I thought he could've come to the door at any time. That was the way you had it in your head.

"So, we were more thinking in terms of, 'What if he's still alive?' It's a very odd thing to grow up thinking of your father that way. You miss out on a lot of things, and then my mom remarried. But everyone would tell me, 'You look just like him.' I would get that all the time, and it was a compliment because he was a good-lookin' guy."

The son, speaking over the phone, chuckled.

Hal joined the Army Air Corps, as it was known during World War II, in 1943, and peace came before his training as a navigator bombardier concluded. However, he remained in the Army Reserve until Elinor received a telegram on his first day at work for Kaiser-Frazer Corporation, which manufactured automobiles just east of Ann Arbor in Willow Run.

"Mom got the telegram and called him," said Downes. "He said he hadn't even sharpened his pencils yet. That was shortly after they'd won the tournament. He graduated, got the job and headed out to Virginia for re-training on the planes he'd be flying. We spent a few months there, and in the fall, Mom saw him off in San Francisco, and we had a lot of letters from his time in Korea to draw upon."

Lt. Downes was in the back of the B-26 Marauder, a twin-engine, cigar-shaped medium bomber, on a night mission when the engines failed and it ended up crashing. His son said all that's known for sure is that two of the four in the plane were captured (pilot John Quinn and Enoch) and that his father and Rennie Campbell, an observer in the plane, were listed MIA. Downes has flown over the area where his father's plane presumably went down.

"He operated the latest bombing technology and the targeting from the back of the plane," said his son. "They hit their target and veered off right then. Two members survived and my dad was behind the bomb bay (door). The pilot and the guy seated next to him had to go out first, and we don't know what he did in terms of letting my dad know.

"So, we just don't know what happened. I often think about the hell he went through. It was perfectly quiet, no communication from the cockpit, and he's deciding, 'Do I jump? Do I not jump?' To think that he just sat in that plane and rode it down in a slow decent -- it wasn't like a nose dive -- or did he try to get out and couldn't get out? It's not the easiest plane to get out of. We just don't know. Did he get out? All we know is that the other two got captured, and at least one died."

Knox said, "It is the wound that never heals."

Their mother had a New Hampshire vanity license plate reading: "HAL-MIA." Above it was the state's motto: "LIVE FREE OR DIE."

Sixty-seven years later, a son and daughter continue wondering what became of their father.

Downes said, "He's probably one of the last ones they'll find because when the government can go back and search for remains, they are focusing on major battlefields rather than downed planes that are scattered.

"I think the last thing my dad would've wanted would be for me to spend my life looking for him, but that's not all that I've done. But it has played a big role in my life."

Their interest in tracking down their father and others heightened in 1992, when Russian president Boris Yeltsin said that some U.S. POWs from World War II and the Korean War were taken to labor camps and imprisoned in what was then the USSR. Rick and Donna theorized that their father, who had knowledge of technology the communists did not have at the time, might have been taken there and forced to teach it to Soviets.

Knox left her law practice and founded the Coalition with others, and Downes eventually succeeded her as president when she had to focus on the care and treatment of Cecil, who died of cancer. Downes took part in negotiations for the return of the remains of U.S. servicemen in recent years, but he said his father has yet to be located. Downes flew to North Korea with Vice President Mike Pence and was part of a group headed by New Mexico governor Bill Richardson.

Brother and sister live right across the Piscataqua River from one another with Downes in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Knox in Eliot, Maine. They remain close and also share a love of writing. Knox is working on a "historical fiction" with her father as the main character, who was taken prisoner during war and transferred to Russia.

Rick (left) and Donna in front Hal's image etched into the Korean War Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Downes wrote on the website for the Coalition of Families of Korean and Cold War POW/MIAs:

"Soldiers sent into battle face dire realities. One of these ends in the possibility that, like disappearing into a Stephen King fog, he or she will simply never be heard from again.

"This kind of enigmatic loss ripples through generations of the man or woman's family. There is no ending to their story. There is no grieving to begin healing. There is only uncertainty, longing, and an ever-present hope that he or she will return one day.

"It is a wound that never heals."

That is the familiar refrain to their deep loss and never-ending uncertainty.

The lieutenant also left behind a father and three sisters. Hal was the second-oldest in the family, and his father worked in accounting while raising a young family after his wife died when Hal was 8.

"Those three sisters loved the heck out of him," said his son. "Talking about my dad never ends for me. It's another opportunity to spend some time with him. I write some about what me and others in this situation would be doing in life now had this person not been missing.

"There was so much that went on in the life of a guy who was playing goalie for the University of Michigan, and less than a year later all of this happened."

They cherish a brief video compilation of their father's life, titled "Forever Young," spliced together from home movie reels.

"It has my mom and dad together singing," said Donna. "That's the only time I ever heard his voice, and he had a really thick Massachusetts accent. It ruined my whole image of him."

Donna laughed and added that she has another visual of Dad that came in the form of a birthday gift Rick had another family member draw as a "portrait-sized" pencil sketch.

"It's of my dad wearing his No. 1 Michigan jersey," said Donna, "and me on his lap. Of course, it was superimposed. They took separate photos of both of us and made one of us together. Obviously, I have to disclaim that we never were actually together.

"It is one of my cherished pieces because it has always made me sad that my dad never met me, never held me."

Donna had two children with Cecil. Their son, Dru Knox, 28, who got his grandfather's dimples, has worked in a technology-related field and recently become enamored with writing. Their daughter, Kirstyn Lipson, 33, is married and has a son who turned 1 in September. Charlie Knox Downes Lipson is the great-grandson of Hal, and the beginning of a third generation since he's been missing.

Willard Ikola sat out his freshman year of 1951, as was required then, and learned from Downes before replacing him as goalie the next season. Ikola also won a national championship before earning a silver medal as the outstanding goalie in the 1956 Olympics. He became a legendary high school coach in Minnesota, where one of his top students of the game was current Wolverines coach Mel Pearson.

And so the "circle of life" in Michigan hockey continued, too, while Downes remained missing in action, a hero in every way who will make the Hall of Honor that much more of a special place. His children will be there to accept on his behalf, with hearts that will surely be heavy as well as they are full of love and pride.