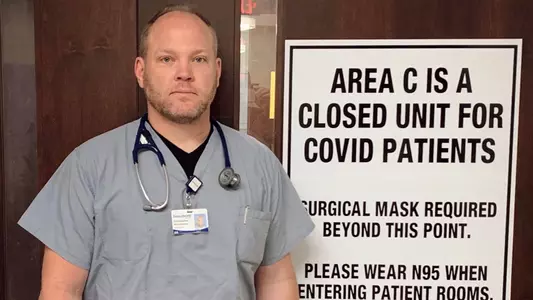

Dr. Chris Hutchinson Provides Moving Insights Into Battling COVID-19

3/25/2020 4:20:00 PM | Football, Features

By Steve Kornacki

PLYMOUTH, Mich. -- When Chris Hutchinson returned from a spring break vacation in Naples, Florida, with his family and resumed work as an emergency room physician at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan, he arrived just in time for the COVID-19 pandemic to reach the doorstep of his workplace.

"We saw one COVID patient per shift for a few days," Hutchinson recalled of March 9-10. "Then, there were many each shift. And a few days after that, it was pretty much all we were seeing come in.

"That was when we had drive-through testing set up, and the first day we saw 50. Next day, we saw 100. The next day we saw 200, and then in two or three days we saw 300 people coming through the drive-through."

Hutchinson was an All-America defensive tackle and a captain for the University of Michigan football team in 1992, and his decision to become a doctor was sparked by an anatomy class his sophomore year. He initially deferred his entrance into Michigan's medical school as a free agent with the NFL's Cleveland Browns, but during rookie camps with the Browns that spring, he decided his best future was in medicine. He canceled the deferment and was in classes that July.

What a fortunate decision that was for the patients he treats today in a hospital where Hutchinson said 120 of 130 beds are filled by coronavirus patients.

"The interesting thing right now is that for everybody else we were seeing, there is hardly any chest pain, belly pain or stroke patients now," Hutchinson told MGoBlue.com during a phone conversation this week. "Last night, I looked at the track board on people who walked in the front door, and there were 20 people who came in. Eighteen of them had something to do with COVID.

"So, that's all we're seeing, pretty much. It's just one after the other, all day long, and the really sick ones we put in a 14-bed unit that's all under negative pressure so there's a vacuum that sucks the flow of air through the rooms so it goes out, and so all of this air isn't going around and contaminating the hospital. But everybody we see is like this."

He said that with limited available COVID-19 testing materials, the hospital no longer tests for normal flu strains and "only tests people that are either high risk, meaning they have a lot of medical problems" or if a decision has been made to admit them. Hutchinson said one hospital area has been "converted into a COVID holding unit" for those unable to get a bed because all are filled.

"We had a smaller hospital call and tell us they have a COVID-positive patient but are out of ICU beds," said Hutchinson of intensive care units. "We told them, 'Nobody has ICU beds. We can't take your transfer because we don't have very many beds.' We've had to convert other areas in the hospital into ICUs.

"Everyone has to deal with this, and unfortunately we are right at the front end of it, still on the curve -- a steep, upward curve."

Frustrations are building.

Hutchinson said: "I had a 77-year-old woman two nights ago literally get up off the gurney and get in my face, saying to me, 'YOU'RE NOT TESTING ME?' I said, 'No, ma'am, I'm not testing you. You are going home and you're doing good right now. Assume you've got the disease. If you get worse, please come back.' I knew she was anxious and wanted to know for sure. And that's a struggle because our health system has never before turned people down. But you have to meet a certain criteria to get tested.

"A lot of people, we have to say to them, and I say this 20 times a shift: 'Assume that you have COVID-19 and quarantine yourself. If you get worse, you need to come back. But right now, there's nothing that we can do for you.' But because it's so prevalent in our community, anyone who has the symptoms, we're assuming they've got it. But we can't test for it (in all cases). And we assume everyone coming in has it, even if they're coming in for a broken ankle.

"You have to do that because they might be in for the ankle, but after a couple of minutes will say, 'Oh, yeah, and I've been coughing, too.' You're like, 'C'mon, man!' So, now I don't take my mask off all day."

According to the Beaumont Health COVID-19 Patient Tracker for its eight Michigan facilities, here were its statistics as of 3 p.m. Tuesday (March 24):

• Patients with confirmed COVID-19 currently in a Beaumont hospital: 441

• Patients with confirmed COVID-19 sent home: 392

• Total confirmed positive: 833

Hutchinson is on the front lines of a worldwide pandemic and must take considerable steps to protect himself.

"I wear that mask and goggles," he said. "I take them off to eat and drink, and that's it. I have them on in front of the computer, in the patient's room. They never come off. And if you have someone who has it, there is a cart in the hallway in front of their room. I have to sign in to their room and close the door. You'll put a hair bonnet, gown and gloves on before you talk to the patient.

"But now we'll actually talk to them on the phone in their room to get their history. When you have to actually touch them, that's when you go into the room so you can limit your time in the room. And when you leave, the gown, gloves and hair bonnet all goes in either the garbage or the bin to be washed. And that's how it is in almost every single room.

"But then we've tested someone who ends up testing positive for COVID, and that room is offline for one hour after the patient leaves it. They let all the air settle to the ground and sucked up into the vents. Then, environmental (workers) come in and clean it head to toe to reduce the transmission to the next patient."

Hutchinson, and health-care professionals from the University of Michigan Hospital to facilities across the state and the entire globe, are going to work daily in extremely high-risk environments to perform potentially life-saving acts. Vice President Mike Pence termed them "extraordinary and courageous."

"You knew when you decided to get into emergency medicine that there was the potential for disasters and mass casualties and all these sorts of things," Hutchinson said. "But unless you were in Boston or 9/11 or Las Vegas (for massive attacks), you don't really know what this is like. And no one's ever been through anything like this before.

"So, at some point, you have to say, 'This is what I signed up for.' I just have to put my head down and do my job. You can't really think too much about how you're being exposed because it's going to drive you crazy. You have a job to do; just do it. Get down and go."

His son, Aidan Hutchinson, a rising junior and a rising star defensive lineman for the Wolverines, is following in his father's footsteps that have the cleat marks. His youngest daughter, Aria, is following in his footsteps that led to Michigan's med school and is a Michigan junior applying there.

He's inspired his children as surely as his mother, Nancy, planted the seed in his mind as a now-retired emergency room nurse in his hometown of Houston. That seed began taking on roots during his sophomore year at Michigan.

"I took an anatomy class and it really clicked," said Hutchinson, a kinesiology major. "That's when I knew health care was where I was going to go. When I made it through (several tough classes), I thought, 'There's no way I can't do this.' But that anatomy class was a major fork in the road for me that sent me down this path."

Chris Hutchinson during his playing days as a Michigan defensive tackle

Meanwhile, he was thriving on the football field. Hutchinson tied Mark Messner's single-season sacks record with 11 in 1992 while setting the record for the most yardage with 99. He redshirted when Messner set the mark in 1988 and proceeded to win five Big Ten championships and finish second in career sacks (24) and yardage (188).

Hutchinson made up for his lack of size (6-foot-2, 249 pounds) with tremendous technique, competitiveness and a high motor. The Big Ten's Defensive Lineman of the Year was not drafted because it was feared he wouldn't hold up against the behemoths in the NFL, but Cleveland signed him as a free agent.

"I knew because of my size and the injuries that I had that at the position I was going to play, I was going to be a tweener," said Hutchinson. "When I got to rookie camp and things go the way they go, you say, 'You know what, I think it's time for something new.' When I was done with rookie camp, I went in and talked to, of all people, (current Alabama head coach) Nick Saban, who was the defensive coordinator. And you know who the head coach was, Bill Belichick (now with the New England Patriots), and I told them of my decision."

He returned to Ann Arbor, called the dean for admissions and began med school, utilizing the NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship he earned as a three-time Academic All-Big Ten selection. He graduated in 1997 and began his career as an emergency room physician.

Hutchinson has seen more COVID-19 cases than he can count in two short weeks, and he offers this advice for everyone:

"Just be patient. We've never experienced the lack of resources we have in this country like we have now: no gowns, no masks, no testing (at some hospitals), and I think that's been very frustrating for a lot of people."

The family has meals together most mornings or nights at their home in downtown Plymouth, about a 25-minute drive east of Ann Arbor. Then Dad jumps on the freeways to go to work on perhaps the greatest challenge this country has ever known. He works what amounts to an average of four lengthy shifts per week. It's stressful, but Hutchinson stresses that it's what he's trained to do.

Still, this is uncharted territory for everyone. How is he holding up?

Hutchison took a deep breath and began, "You know, this affects everyone differently. There were clearly some people on edge that I was working with. Everything is different, and every day something clinically significant changes -- either how we do it or the virus or what the shortages of masks or gowns are. Every single day, something is different, and you can't get into a routine.

"So, that's been the hardest part of it. The routine is a lack of routine, and when you can't get into a routine, that, for me, is the most stressful part."

Hutchinson also is an assistant professor at the Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine and works two days each month at Harbor Beach Community Hospital, a small critical access facility near the tip of Michigan's thumb area and along the shores of Lake Huron, where there is no COVID-19.

"Not yet," cautioned Hutchinson. "There will be."

The Hutchinsons (from left): Chris, Aidan, Aria, Melissa and Mia on spring break earlier this month in Naples, Florida

There wasn't even a single reported case in the metropolitan Detroit area when he returned from spending spring break along with Gulf of Mexico coast with his wife, Melissa, a Michigan graduate and former high-level fashion model who now is a thriving professional photographer, oldest daughter and Michigan grad, Mia, now a product specialist for Chevrolet, Aria and Aidan.

However, now the auto shows Mia works and spring practice for Aidan and his teammates have been canceled. Aria and Aidan are taking classes online and Melissa is working from home. Aidan is going to a high school weight room and playing catch and working out with former Dearborn Divine Child teammate Theo Day, now playing quarterback for Michigan State.

Chris, the doctor in an emergency room just north of Detroit, drives nearly 30 miles to Royal Oak to fulfill his calling.

"Medicine is so challenging," said Hutchinson. "It's not like being in the weight room or on the field. But intellectually, physically and emotionally you (gain) from it (football) because it puts you in uncomfortable situations.

"That's where my mentality right now comes from. I just put down my head and go. I've got a job to do and can't think about anything else."