John Ferrara's 9-11 Hero

9/11/2009 12:00:00 AM | Football

Sept. 11, 2009

By Richard Retyi, U-M Athletic Media Relations

It was a beautiful Tuesday morning in New York City, September 11, 2001, a morning like any other for eighth-grader John Ferrara. John lived in a close knit Italian community on Staten Island, the kind of place where, despite its size, everyone looked out for each other.

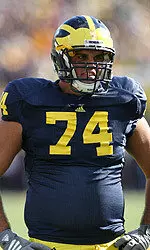

"My childhood was about good food and rooting for the Yankees," Ferrara, now a redshirt senior offensive lineman, says.

It was a regular Tuesday. John had gym class to look forward to that morning and a football game later that week. Across the city, New Yorkers began their mornings the same way, with petty annoyances and little pleasures on their minds. After a rainout the night before, the Yankees' magic number stood at eight. Later that night in the Bronx, Roger Clemens would try to become the oldest 20-game winner in major league baseball history against the visiting White Sox.

John's father, Tony was already downtown working at police headquarters at One Police Plaza. A law enforcement veteran, John worked within spitting distance of the Brooklyn Bridge, a short walk to the Hudson River and just five blocks from the impressive twin towers of the World Trade Center. It was a regular morning for both Ferraras.

At 8:21 a.m., the transponder on American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston to Los Angeles stopped transmitting. At 8:24 a.m., the plane made a 100-degree turn south towards New York City. Twenty-two minutes later, the Boeing 767 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

|

John knew something was wrong. School administrators knocked on the classroom door with looks of concern on their faces. They took students out of the room one by one. He could hear kids crying in the hallway. There were rumors that something big and horrible had happened downtown. In gym class, John learned that planes had hit the World Trade Center and the United States was under attack. He thought of his father, just blocks away at police headquarters. Classmate Eric Olsen, now a senior offensive lineman at Notre Dame, also worried about his dad, a New York City firefighter.

From headquarters, Tony heard the first plane hit the World Trade Center and was close enough to feel the heat of the second plane exploding through the South Tower. He did his best to get people to safety, many unable to do anything but stare with a hand over their mouth. Tony watched both buildings fall.

The cafeteria was chaotic. There was crying and whispers of terrible rumors. Frantic parents streamed into the school to take their children home. Teachers abandoned their lesson plans. The rest of the day was a haze. John overheard students talking about planes hitting the World Trade Center and the towers collapsing. Hundreds, maybe thousands were dead.

John's mother, Linda, picked him up in front of the school at the end of the day. She told John everything she knew about the attacks and calmed his fears about his father. Someone had seen Tony safe after the planes had hit, though no one could reach him and his father had not called. Was he inside the towers when they collapsed? The family feared the worst. Each time the phone rang, everyone jumped. It was never Tony.

Tony was safe. After the towers fell, his priority was the security of police headquarters and the immediate recovery effort. It wouldn't be until late that night that he would have a chance to call home to tell his family that he was okay. They wouldn't see him for another day as Tony joined emergency services and the recovery efforts at Ground Zero. He dug through the mangled piles of concrete and steel looking for survivors, covered in ash and reeking of burning jet fuel.

|

When he finally returned home, John hugged his father tight, relieved that he was alive. Exhausted, his father went to bed only to wake up at 6 a.m. the next morning to return to Ground Zero to continue the recovery efforts. For the rest of the month, Tony woke before dawn and returned long after dusk, dragging himself to bed physically and emotionally exhausted.

"He did what he had to do," says John, the working class son showing stoic admiration for his working class father.

John's neighborhood suffered many losses during the tragic attacks but the close-knit community healed as a family.

"I think about the lives lost and feel the sadness of it," says John. "It's tough for people to understand the magnitude of what happened. New York is a special place and even though it's huge, we're a very close community."

John's father honored the family with his strength during and long after one of the greatest horrors of his lifetime. This September 11, eight years after the tragedy, the Yankees are nine games up on the Red Sox in the East and Derek Jeter is a single away from becoming the Yankees' all-time leader in hits. Tony and the Ferraras are in Ann Arbor, ready to see their son play for the University of Michigan in one of college football's greatest rivalries. The memories of that day will never be forgotten, but the Ferrara family bonds have never been stronger.