Once-in-a-Lifetime Team: '59 Wolverines Exceeded All Expectations

9/26/2019 1:50:00 PM | Men's Swimming & Diving, Features

By Steve Kornacki

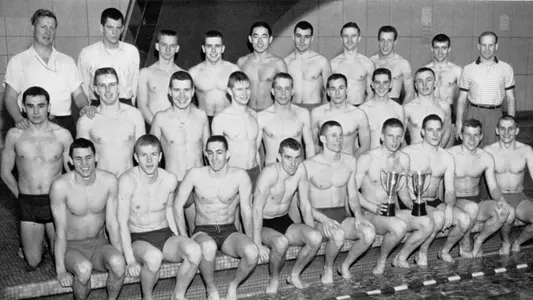

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- Sixty years have passed since the University of Michigan men's swimming and diving team dominated the NCAA meet in an almost unfathomable manner. The 1959 Wolverines scored 137.5 points, shattering the previous record of 96.5 points and topping the point totals of the second-, third- and fourth-place teams combined with 17 points to spare.

It was a complete and total dunking, and by the final event, Ohio State's swimmers were chanting, "Let's Go Blue!" Those Buckeyes were pulling for Michigan to win the 400 medley relay so OSU could finish second ahead of Indiana and Yale. And those Wolverines obliged.

They won the third consecutive NCAA title for Coach Augustus "Gus" Stager in such convincing fashion that at least one swimming historian considers them the "greatest" team the sport has ever produced.

SwimmingWorld.com posted an article about them in May with the headline: "'59 Michigan Team Still 'The Greatest of 'Em All.'" It was written by Bruce Wigo, an historian and senior consultant at the International Swimming Hall of Fame, which has enshrined four from that team.

» Read: '59 Michigan Team Still 'The Greatest of 'Em All' (PDF)

Scoring methods and the number of events in the NCAA meets have gone up, and so comparing point totals no longer works. But there's no denying that Wolverine team -- which had 17 of 20 members score points -- has stood the test of time where greatness is concerned.

"We exceeded all expectations," said Frank Legacki, who won the 100 freestyle. "We knew we had a good chance to win the NCAA, and everybody swam well -- everybody. So, we scored more than the next three teams combined. No team has ever dominated like that, certainly in swimming. It was very special; it was very gratifying to be a part of. We set a lot of high standards.

"It was a team with a lot of diversity. But everyone was very focused. We knew what we had to do. It was very single-minded. We also got some great leadership from our senior captain, Cy Hopkins (a first-place finisher in 1957 in the 200 breaststroke). He finished second for Rhodes Scholar and was a bright guy."

Cy Hopkins receives instruction from Gus Stager

Jon Urbanchek, who finished second in the 1,500 freestyle as a sophomore that year and went onto become one of Michigan's winningest coaches, said, "That was an unusual team -- a once-in-a-lifetime team. It was an unbelievable assemblage of young talent."

Dick Kimball, one of three divers who placed in the top six in the two springboard events and then became a legendary diving coach, recalled: "Gus, in a big meet, was an excellent guy to get you fired up. And what we did was largely because Gus and (diving coach) Bruce Harlan recruited so many people that were really good."

Kimball finished fourth in both springboard events in 1959, but won both the one- and three-meter dives in the 1957 NCAA meet.

Many of those swimmers and divers -- now over 80 years old or very close to it -- are returning to Ann Arbor to have a reunion Friday (Sept. 27) followed by recognition the next day at the Michigan-Rutgers football game, and completed on Sunday with a "Celebration of the Life of Gus Stager," at the Michigan League.

Stager died July 6 at the age of 92, and his boys are coming back to remember him and rekindle their own friendships and memories.

That powerhouse team would have both of its coaches inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame, and Kimball and Urbanchek also were enshrined for their coaching accomplishments.

Urbanchek led the Wolverines to 13 Big Ten championships and the 1995 NCAA championship during 22 seasons, 1983-2004. He was 163-34 in overall dual meets, and set a school record with a .962 winning percentage (100-4) in conference duals. Urbanchek also was a seven-time assistant coach on the U.S. Olympic swimming team.

Kimball began coaching divers for Stager in 1959-60, taking the place of Harlan, who died tragically when falling 27 feet while attempting to dismantle a diving board in Connecticut on June 21, 1959. Kimball stayed at Michigan for 43 years, producing four Olympic gold medalists and coaching U.S. divers in five separate Olympics, including 1984, when his son, Bruce, was a silver medalist.

"Kimball and myself were part of that unbelievable team everyone talks about," said Urbanchek. "But what's unbelievable now is that it was 60 years ago!"

They both learned from a master.

Stager became the second legendary swimming coach at Michigan, succeeding his own mentor, Matt Mann, in 1955, and stayed 26 seasons in that position, producing three Big Ten and four NCAA champions (1957-58-59-61). He was 188-40-1 in dual meets and coached the 1960 U.S. Olympic team.

"First of all, Gus was pretty smart," said Legacki. "He was a high school math teacher, and he had such a good grasp of the techniques and everything. But he also had great energy and enthusiasm. I think he worked and trained us a lot harder than most, and it felt good to do that. We knew we were building something and he really drove us in a constructive and positive way."

From left: Stager, John Smith, Hopkins, Tony Tashnick and Legacki

Stager was pulled while fully-clothed into the Teagle Pool at Cornell University by his joyous swimmers and divers, a longtime sport tradition, after their '59 triumph.

Harlan combined with Stager to form an unrivaled recruiting duo, and then coached them up into champions.

Kimball said: "Bruce Harlan was a great coach. He was amazing. And, ironically, he never dived until he was in the Navy during World War II. He knew everything about diving."

Harlan won a gold medal in the three-meter springboard and a silver medal in the 10-meter platform dive at the 1948 Olympics in London.

Urbanchek said Stager and legendary Indiana University coach James "Doc" Counsilman revolutionized swimming with interval training adapted from European track and field techniques.

"Gus and Doc were the pioneer coaches in America," said Urbanchek. "They started the interval training, which is how we train today. You would train by swimming 100 yards 15 times instead of just swimming a mile, and it was a physiological change in training. They got ahead of everyone else and became great rivals because they were clever.

"So, we were pioneers. It was a new philosophy. You trained your body to your race. It was called 'race pace' training, and that's how we got ahead of the curve. In my job here, I wanted to create the same environment at Michigan that Gus created for us."

Urbanchek also became a pioneer coach with techniques such as altitude training.

"I would not be here today if Gus did not offer me a scholarship," said Urbanchek. "I was a poor immigrant (from Hungary). My parents could not afford a school like Michigan, and Gus gave me an opportunity. I was a good enough swimmer to get that."

Urbanchek was part of an amazing sophomore class that included two of the three 1959 swimming first-place finishers in Legacki and Dave Gillanders, who won the 100 and 200 butterfly, respectively. Gillanders, a bronze medal winner in the 200 fly at the 1960 Olympics, also set the world record in that race.

Senior Dick Hanley was the other swimming superstar on the squad. He won the 220 free as well as swam on both national championship relays in '59, and had won a silver medal on the U.S. 800 freestyle relay in the 1956 Olympics, when he also finished fifth in the 100 freestyle.

That Michigan team had a startling number of All-Americans, 18 in all: Ron Clark, Al Gaxiola, Joe Gerlach, Gillanders, Hanley, Hopkins, Harry Huffaker, Kimball, Legacki, Ernest Meissner, Andrew Morrow, Ed Pongracz, John Smith, Tony Tashnick, Tony Turner, Urbanchek, Bob Webster and Carl Woolley.

The Wolverines wrapped up the '59 meet by taking the 400 medley relay with John McGuire, Woolley, Hanley and Legacki, and with the Buckeyes and others cheering them on: "Let's Go Blue!"

Kimball recalled: "Yeah, the Ohio State guys were rooting for us because they would beat Yale for second if we won. That doesn't happen every day (laughter)."

Jon Urbanchek (L) and Stager, who coached and mentored Urbanchek

The Super Sophs scored 73 points together for over half of Michigan's total, and scored 29 more points than the entire runner-up Buckeyes at Teagle Pool.

"I'm the luckiest guy on this earth," said Urbanchek. "To come to America and attend a great university like Michigan that had the best swimming program, and then win four NCAA championships in my five years on campus was really something. I got us some second-place points to help. I was not a superstar on the team like Legacki and some of the others.

"It was just one of those years when I came in that we had an unbelievable assemblage of freshmen. We weren't eligible to compete that first year (as freshmen due to NCAA rules), but swam great as sophomores."

Legacki recalled his winning performance in Ithaca, New York: "The two guys I raced against were national champions the previous year and the year before that. It was (Donald) Patterson of Michigan State and Gary Morris of Iowa. We'd swim against each other in dual meets during the season, and they were good. It was a tough race. I was just fired up and won, that's all, just swam like hell.

"I was always a respectful competitor, we shook hands. But I came from a different background than most swimmers. I grew up in Philly (Philadelphia). When I got up on the blocks, I would tip my head to the guy next to me."

Then Legacki would say something to intimidate the competition, but would do so in a way that it would bring a chuckle. It was gamesmanship, and he'd learned how to get into the heads of others growing up in a tough urban setting.

Legacki has homes in Ann Arbor and Stuart, Florida, where he enjoys fishing. He graduated from Michigan and also got his MBA at the school. He received recommendations from Michigan athletic director Fritz Crisler, then track and field coach Don Canham and chairman of the Board of Regents Gene Powers before getting accepted in the post-graduate program. He had a software company with his wife and other successful business ventures before retiring.

Urbanchek said four members of that talented sophomore class have passed away, and he was saddened that his "best friend" from that team, distance freestyle swimmer Jack Pettinger, died last year. Urbanchek said Pettinger was a great student and helped him, while he was mastering English, to the point where Urbanchek joked, "Jack's name should be on my diploma." Urbanchek added that the way they helped one another away from the pool led to how well they bonded in it.

Pettinger went on to assist Counsilman at Indiana before becoming the longtime coach at Wisconsin.

"It was an amazing combination of people," said Urbanchek. "They all went on to become successful and influential in the academic world, as doctors, a Navy Seal in Ron Clark who also went on to become a doctor, a hand specialist. It's a great group of people. We're all proud."

Urbanchek rattled off one successful teammate after another. For all they accomplished in that pool in Ithaca 60 years ago, they did much more after that, going onto successful careers and having families.

Their legacies went beyond the pool, but what they did together in one was the stuff that makes legends.